Filtering and State Estimation

Implementation of Bayesian filtering algorithms, including EKF, regular + Augmented UKF, and Particle Filter.

This project was associated with Northwestern University ME 469: Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Robotics.

Introduction

Objective

The goal of this project was to implement various Bayesian filtering algorithms for controlling a simulated differential drive robot, and compare their results. Included are implementations of the extended Kalman filter (EKF), regular and augmented unscented Kalman filter (UKF), and particle filter. A dataset containing ground truth robot paths and landmark measurements was provided as part of the course.

Motion and Measurement Models

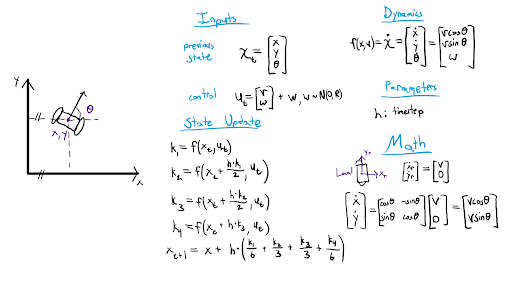

The motion model used in this project is as a simple implementation of a planar wheeled robot’s nonlinear dynamics. As dictated by the provided control signal trajectory, the inputs to the motion model consist of forward and angular velocity commands, as well as the robot’s state at time t. The control signals are passed into the robot’s time-invariant nonlinear dynamics to produce changes in its state, which consists of x-y coordinates and a heading angle as measured from a line parallel to the global x-axis starting at the robot’s 2D centroid. The model is nonlinear because the robot’s velocity in the global x and y directions are dependent on the cosine and sin of the robot’s heading, respectively. The state update occurs through a typical 4th-order Runge-Kutta (RK4) integration scheme. The motion model outputs the robot’s new state at time t + h, with h being the simulation timestep. RK4 was chosen over a method such as Euler integration because of its superior accuracy. Gaussian noise is added to the control signal before being propagated through the nonlinear dynamics for a more robust representation of uncertainty in the system. This noise vector can be set to zero to recover the deterministic state update. The motion model math is in the figure below.

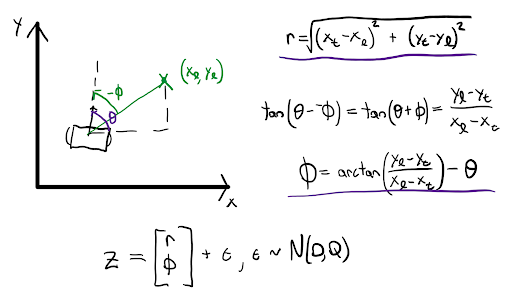

The measurement model is a simple range-bearing model, meant to imitate the use of a camera for identifying and taking measurements of known landmarks. Because the robot is given ground truth landmark positions, the range can be calculated with Euclidean distance and the bearing can be calculated using simple trigonometry. Gaussian noise is added to the measurement to imitate the uncertainty present in a realistic sensor. The deterministic measurement model can be recovered by removing the Gaussian noise. The measurement model math is in the figure below.

Augmented UKF

The UKF is a version of the Kalman filter that allows for nonlinear dynamics and measurement models. Instead of linearly approximating these models like the EKF, the UKF takes advantage of sampling as well as the assumption that both the prior and posterior distributions are represented by Gaussians to develop a more robust estimate of state. The Gaussian assumption allows a fewer number of samples to be used, as opposed to a non-parametric filter like the particle filter.

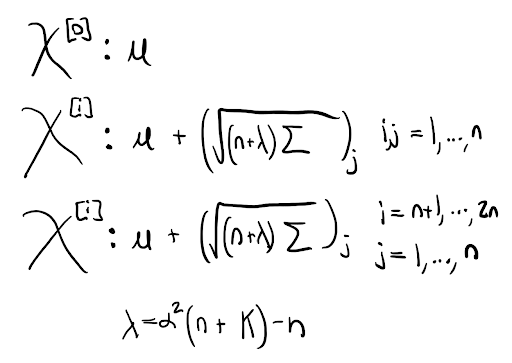

The UKF is made up of four major steps: sampling, prediction, resampling, and measurement update. In the sampling step, samples (called sigma points) are selected in order to best preserve the Gaussian prior with a minimal number of points. The first sigma point is always the mean of the prior, and the subsequent sigma points are selected based on the square root of a matrix proportional to the prior’s covariance. The matrix square root is implemented using a Cholesky decomposition. This results in 2n + 1 sigma points, where n is the dimension of the state vector. The sigma point sampling process can be seen in the figure below.

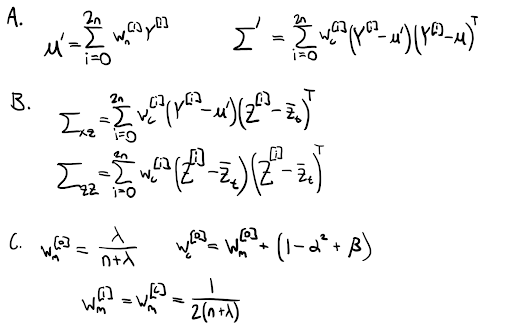

Next, the sigma points are passed through the motion model to generate a set of transformed sigma points according to the nonlinear dynamics. The unscented transform allows for the recovery of the predicted mean and covariance from this transformed set through a weighted averaging process,. If there is no new measurement, the predicted mean and covariance are used as the best estimate of state and passed through the UKF at the next timestep.

If there is a new measurement available, it can be used to update the predicted belief. First, new sigma points are sampled from the prediction at the previous step. These sigma points are passed through the measurement model to produce a transformed set of measurements from which mean belief and covariances can be extracted. Finally, the belief update occurs through the typical Kalman filter update. This math can be seen in the figure below.

The version of the UKF included in the original paper is sometimes referred to as the augmented UKF [2]. The augmented UKF algorithm involves an augmented state and covariance matrix, which incorporate the process and measurement noise into the sigma point sampling process. The augmented UKF also propagates this noise through the nonlinear models. The implementation of the augmented UKF is almost identical to the regular UKF except for two key differences: 1. The number of sigma points is now 2n_aug + 1 where n_aug is the dimension of the augmented state vector and 2. The transformed state/measurement and respective noise are separated after sigma point generation and passed through the nonlinear models together. The version of the UKF in this project can optionally be turned into the augmented UKF, and a comparison of the two methods will be made later on.

Results

Experimental results show that the augmented UKF not only smooths a lot of the visible path oscillations and inaccuracies, but also provides more consistent results for varying levels of noise. The augmented UKF follows the shape of the ground truth trajectory much more consistently, and even when it deviates the differences are comparatively small.

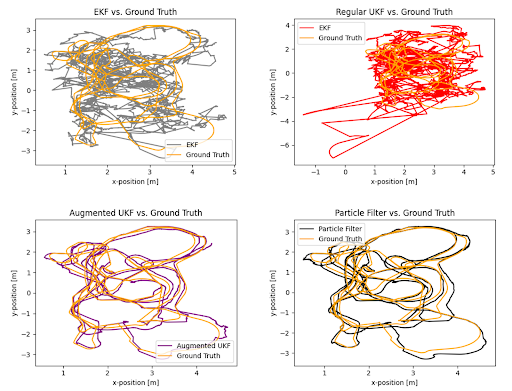

In addition to the UKF and augmented UKF, the same dataset was tested on custom implementations of the EKF and the particle filter. The EKF slightly outperformed the regular UKF, with comparable error but higher path correlations. The augmented UKF and particle filter had comparable results, with both filtered paths having high accuracy and low amounts of noise. It is worth noting that the particle filter had negligible performance gains for significant computational costs, taking far longer to run than the augmented UKF despite using only 50 particles. The EKF’s performance sat in between the UKF and augmented UKF, but was far more lightweight because the Jacobians required were computed analytically and only evaluated during runtime. This could serve as a decent filtering option when motion and measurement model Jacobians are simple enough to compute by hand, but ultimately the augmented UKF seems to be the best choice out of the set. The figure below displays a comparison between all filtering algorithms and the ground truth path.

One possible explanation for the augmented UKF’s performance gains is the inclusion of the process and measurement noise in the sigma point sampling process, and the subsequent propagation through the nonlinear models. By including the noise representation as part of state, the drawn sigma points may provide a more well-rounded representation of the underlying distribution. Additionally, because of the augmented state’s increased size more sigma points are sampled. It is possible that the improved performance is partially a result of the larger sigma point set size allowing a better representation of the prior. Finally, because the noise is sampled alongside the state, it can be used as an input to the nonlinear motion and measurement models. This may allow for a more realistic representation of the noise’s effect on real hardware, aligning the predicted path with the ground truth. The augmentation of the covariance matrix likely has a similar effect.